Halo Players Biographies

Matt Leto should be in a six-figure income by year's end

January 17, 2005 The New Video Game Super Stars Biographies Below:

Back to: Walter Day Conversations

Go to: Paul Dean Biography

Back to Golden Era Index

Video Game Players are making big money!

What is this phenomenon going to be all about?"

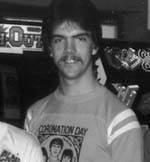

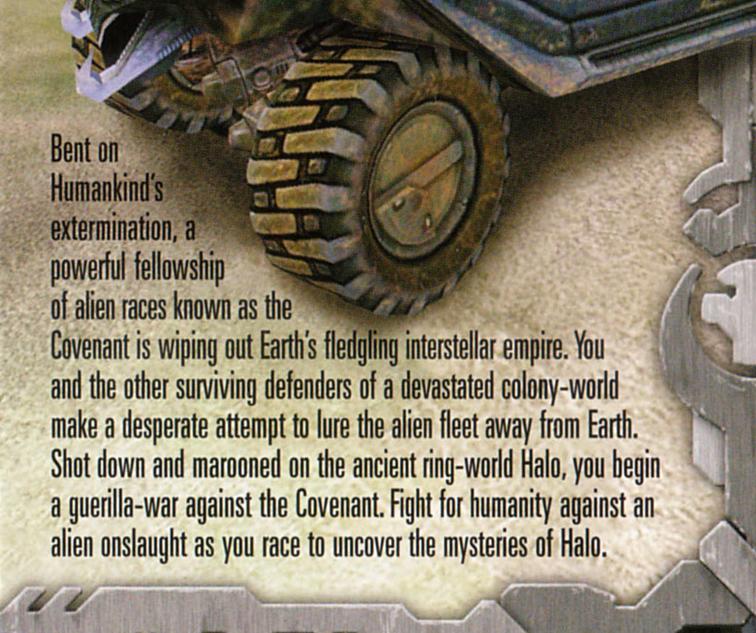

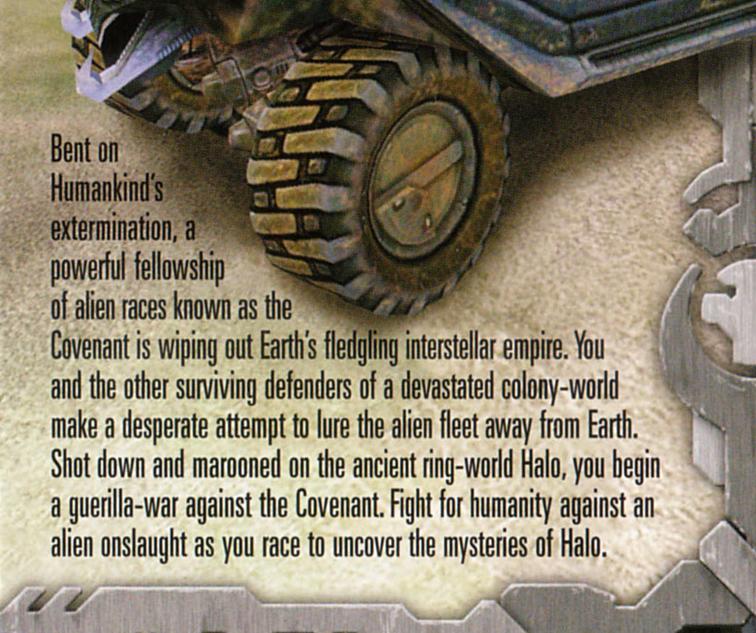

World Champion, Matt Leto Playing Halo at home.

With over 800 records he is deemed the best overall player in the world.

Billy Mitchell is the old school gamer and after 25 years of video game playing it looks like

we have a changing of the guard. Welcome Matt leto, the New Millinium World Champion!

Matt Leto should be in a six-figure income by year's end

January 17, 2005 The New Video Game Super Stars Biographies Below:

Back to: Walter Day Conversations

Go to: Paul Dean Biography

Back to Golden Era Index

[My Biography] [Masters Tournament Article]

[Coin-Op World Records]

Video Game Players are making big money!

What is this phenomenon going to be all about?"

World Champion, Matt Leto Playing Halo at home.

With over 800 records he is deemed the best overall player in the world.

Billy Mitchell is the old school gamer and after 25 years of video game playing it looks like

we have a changing of the guard. Welcome Matt leto, the New Millinium World Champion!